Hey guys, in this blog post, we’re going to perform a security assessment of a smart contract and, with the help of Certora’s formal verification tool, try to prove there are no “High” severity issues residing in the source code.

Per sherlock rules a “High” severity issue causes the protocol or users to lose more than 1% and more than 10$ of their principal/yield/fees without extensive limitations of external conditions.

Modern audit contests

First of all, a few notes regarding modern audit contests.

Sherlock is a great audit contest platform per se. We actually ran an audit contest with Sherlock, and the final audit report was pretty solid. It’s been almost 2 years, and the audited protocol has not been hacked and hopefully won’t be. But, like all such platforms, they don’t give a 100% guaranteee that there’re no bugs missing (here we’re talking only about “High” severity issues).

Modern audit contest platforms have a couple of drawbacks. First of all, they pretty much limit the auditors with the time given for the audit. If you take a look at the latest aaveV4 audit contest, you may find that the audit scope is 3614 nSLOC, which is basically 7k lines of code. So every day you have to audit ~242 lines of code, which is pretty much a race. The formal verification approach presented in the current blog post does not fit well with audit contests because it thoroughly checks all of the protocol methods and invariants, thus requiring way more time than 29 days. But in the end, if your protocol’s TVL is 55 billion dollars (shout out to Aave), then it does make sense to spend more time on the security audit.

Another point is that protocols that reach Sherlock (or other audit contest platforms) to perform an audit contest are already pretty much covered with unit and statefull fuzzing tests, which greatly reduce the chances of finding anything higher than “Medium”, so in the end, such audits end up with infinite escalations and arguing with lead senior judges over subtle discrepancies in the readme file, with the only purpose to keep your reported “almost” medium severity issue as a valid finding per Sherlock (or other audit contest platform) rules.

Protocol types and invariants

If you check Solodit, you may find that they divide the whole DeFi protocol landscape into 34 categories:

1. Algo-Stables

2. Bridge

3. CDP

4. Cross Chain

5. Decentralized Stablecoin

6. Derivatives

7. Dexes

8. Farm

9. Gaming

10. Indexes

11. Insurance

12. Launchpad

13. Lending

14. Leveraged Farming

15. Liquid Staking

16. Liquidity Manager

17. NFT Lending

18. NFT Marketplace

19. Options

20. Options Vault

21. Oracle

22. Payments

23. Prediction Market

24. Privacy

25. RWA

26. RWA Lending

27. Reserve Currency

28. Services

29. SoFi

30. Staking Pool

31. Synthetics

32. Uncollateralized Lending

33. Yield

34. Yield Aggregator

Next, if you start checking all “High” severity issues from solodit for the last 20 months (3512 “High” severity issues), you may find that, at some point, they start to repeat. If you try to reduce the repeated issues even further, you may find that all of them are actually about broken invariants like getting more or fewer assets than expected, bypassing require() statements and so on.

Typical invariant violations from solodit are:

– Single method DoS

– Protocol insolvency

– User/protocol gets more/fewer assets (tokens, votes, etc…) than expected

– Funds (native tokens, ERC20, ERC721, etc…) are stuck in the contract

– Bypassing a single require statement (like daily loss limit or max allowed deposit)

– User can get assets more easily (like win a proposal with fewer assets than required, or mint a unique game NFT with fewer assets than required, or with a greater winning probability)

– Admin protected method callable by none-admin roles

– MEV (frontrunning, sandwiching, backrunning)

So each security issue in a smart contract is actually a broken invariant.

Invariant types

There are at least 2 great approaches of how to think about invariants so that they could cover the whole protocol.

Devdacian

The 1st one is presented by devdacian.

Contract lifecycle can be broken into:

1. Construction/initialisation

2. Regular functioning

3. End state

Invariant categories:

1. Black box (can be clearly seen from the docs)

2. White box (based on the internal code)

Invariant types:

1. Relationships between inter-related storage locations (ex: the sum of all values in a mapping must be equal to another storage variable)

2. Monetary value and solvency (ex: contract must always be able to cover liabilities)

3. Logical invariants that prevent invalid state (ex: protocol must never enter a state where the borrower can be liquidated but can’t repay)

4. DoS (ex: liquidation should never revert with unexpected errors such as array index out of bounds, under/overflow, etc…)

Certora

Certora offers an industry-leading tool called CertoraProver that helps in performing formal verification of smart contracts.

They divide invariants into these categories:

1. Valid states (usually a certora invariant)

2. Valid state transitions (usually a certora rule)

3. Variable transitions (usually a certora rule)

4. High level properties (usually a certora invariant)

5. Unit test (usually a certora rule)

Valid states examples

– If the meeting is pending, then it has not yet started

– If the meeting has started, then it is not pending

Valid state transitions examples

Valid state transitions type invariants verify 2 things:

1. Valid states change according to their correct order in the state machine

2. Transitions only occur under the right conditions, like calls to specific functions or time elapsing

For example:

1. Get the state before

2. Run an arbitrary function

3. Get the state after

4. Assert:

– If the state before was 0, then the state after can be 1 or 0 (not 2, 3, etc…)

– If the state before was 0 and the state after is 1, then a certain function selector was called

Variable transitions examples

– After calling deposit(), the balance of all users and the total system balance must not decrease

– After calling withdraw(), the total system balance must decrease

High level properties examples

– If a client makes any operation within the bank system (currency conversion, transfer between accounts, etc…) the total balance of all clients’ accounts must remain the same (i.e. solvency)

– The balance of any single user must be no more than the total funds of the bank

Unit test examples

– The transfer in the system must increase the recipient’s balance by a specified amount and decrease the sender’s balance by the same amount

– In ERC20, if increaseAllowance() was called, the allowance of the spender by the owner increases exactly by the specified amount

Overall certora offers a pretty comprehensive approach in building invariants that cover the whole system although this blog post offers even simpler approach with only “unit” and “high level” invariants because in the end the “valid states”, “valid state transitions” and “variable transitions” invariant categories can be further reduced to “unit” or “high level” invariant categories.

Invariants checklist

Let’s simplify Certora’s approach to building invariants.

Invariants can be divided into 3 categories:

1. High level

2. Unit test

3. MEV

High level category should be applied if your invariant verifies more than 1 contract method (via Certora invariants or parametric rules).

Unit test category should verify a specific method (both state changing and view ones) in 4 ways (you’ll see later an example):

1. Integrity – method updates storage as expected

2. Revert conditions – method does not revert unexpectedly

3. 3rd party effects – method does not affect storage and states of a 3rd party protocol participant (ex: 3rd party borrow position must not become liquidatable after some state changes)

4. Additivity – calling the method with a single value parameter affects the storage the same way as calling the method multiple times with smaller value parameters (ex: ERC20.transfer(to, 10) changes the storage the same way as calling ERC20.transfer(to, 5) 2 times)

MEV is a special invariant category that checks that frontrunning, backrunning or sandwiching a method execution does not negatively affect a protocol participant or favors a frontrunner.

Here is an invariant checklist that should (ideally) be checked when performing a smart contract security assessment:

1. High level:

– All methods are reachable, there’re no methods that always revert

– Method can not be reentered

– The unchecked blocks never over/underflow

– All 3rd party integrations (chainlink, pyth, LZ, etc…) work correctly and follow best security practices

– There’re no unrestricted delegatecalls

– Solvency, a contract must always be able to cover liabilities. For example:

a) The sum of all user balances must equal to total supply

b) The balance of a single user must not be greater than the total funds in the system

c) Lack of partial liquidations allows huge positions to accrue bad debt if the loan amount exceeds market liquidity (when flashloans don’t help)

– No stuck assets (ERC20, native ETH, votes, etc…) in the contract. We should simulate possible flows from the beginning to the end. For example: user deposits (or overpays), user withdraws, admin withdraws fees, all must have expected balances.

– Randomness follows a normal probability distribution

– All methods must not affect 3rd party entities (users/pools/etc…)

– Flashloans and actions in a single block must not negatively affect the protocol or benefit the user. For example:

a) User takes a flashloan, creates a proposal, votes, executes a proposal and returns a flashloan

b) User stakes and unstakes in a single block

c) User opens a position, undercollateralizes it and self liquidates

– The secondary market does not affect the protocol’s economic

– There must always be at least 1 admin / owner

– Project dependencies do not have known vulnerabilities

– No infinite loops and out of gas errors

– Critical protocol methods must use access control which can not be circumvented. For example: no one must be able to remove anyone from the blacklist.

– If the state variable is changed, then only certain method(s) and access control roles (or users with allowance) are allowed to change it

– External calls are only to trusted contracts and methods

– If a single call does not affect the user, then it must not grief the protocol or other entities’ assets or gas usage (example)

– Two consecutive arbitrary method calls do not favor the user. For example:

a) User calls grantMinterRole() without access control and mint() afterwards

b) User is granted infinite allowance via one of the protocol methods, user drains protocol funds afterwards

c) User calls unrestricted initialiser and harms the protocol

d) Async router (like 1inch) does not consume the full allowance, the malicious user finds a way to transfer not spent allowance. Allowances must be reset after interacting with async routers because they may not consume the whole allowed amount.

– Semantically equal methods must work equally (like executeBatch() and execute() or swap() and swapMultiple())

– Weird ERC20 tokens must not affect operations

– Calling public methods multiple times (for example in a bridge) must not DoS a backend infrastructure

– Inherited contract methods must be used. For example: if the contract inherits ERC20Pausable, then pause() and unpause() methods must be used.

– Integer roundings on asset transfers must always favor the protocol, up for the “user => protocol” flow, down for the “protocol => user” flow

– There must be economic incentives for participants (like liquidation fee or gas refunds)

– System is in a valid state. For example:

a) If the meeting is in the pending state, then it has not yet started

b) User must not be able to vote after voting has finished

– System state transitions are valid. For example:

a) If the state before was 0, then the state after can be 1 or 0 (not 2, 3, etc…)

b) If the state before was 0 and the state after is 1, then a certain function selector was called

– Block environment (like gas fees or timestamp) does not negatively affect participants. For example:

a) When liquidating a small position user must get better rewards than network gas fees paid

b) Early investors get more rewards than late investors

– Always latest proxy implementation is used in case there’re multiple proxies available

– Two async transactions (with a delay between them) do not negatively affect the protocol or participants. For example: the proposal supervisor is the same both on proposal creation and execution.

– Normal user flow equals the same flow after migration of tokens, locks, etc…

– Invalidated assets must not be able to be used in the system. For example:

a) Removed signer can not create valid signatures anymore

b) Blacklisted users can not perform any actions

c) User must not be able to use an invalidated asset (ex: NFT)

– Signature can not be reused across chain / contract (it must include network id, contract address, nonce, deadline)

– Normal protocol flows must equally affect the storage for 2 different users in different block environments. For example:

a) Two different traders must pay the same amount of fees / penalties and get the same amount of rewards / output on swapping the same amount of tokens

– Output assets can not be acquired with 0 input assets. For example:

a) The proposal must be won with at least X amount of votes

b) NFT must be minted with at least X price

c) One active DAO proposal must have at least 1 voted user

d) For a proposal to be executed, a minimum number of validators must cast votes

– A single require statement or if(CONDITION) revert must not be bypassed. For example:

a) Max amount deposited per user

b) User should not be able to transfer assets to the 2nd account and withdraw, thus circumventing require statements

2. Unit test:

– Integrity

– Revert conditions

– 3rd party effects

– Additivity

3. MEV:

– Frontrunning: adversary tx1 does not affect user tx2

– Sandwiching: adversary tx1 and tx3 does not affect user tx2 and does not profit adversary

– Backrunning: adversary tx2 does not affect user tx1

Audit flow

So, in order not to miss “high” severity issues in the protocol, you may follow this audit flow:

1. Quickstart: read the documentation quickstart

2. Deep dive: create unit tests for state changing methods in order to deeply understand how the protocol works

3. Documentation finish: finish protocol documentation

4. Use cases: write typical protocol use cases with assets movement

5. Roles: describe how protocol methods work by role in order to understand how contracts are connected with each other

6. Manual audit: investigate places of interest found during “Deep dive”

7. Solodit: check similar issues at https://solodit.cyfrin.io/, which often appear in the same type / fork of the protocol

8. Static analysis: run slither and aderyn to catch “low hanging” bugs

9. FV setup: init Certora project. When adding a contract to the Certora scene, think about whether the contract is controlled by the user, i.e. can the user deploy a malicious contract (or token with callbacks) or not.

10. FV unit test: create formal verification “unit test” type rules for all methods in order to better understand possible edge cases

11. FV high level: create formal verification “high level” type rules using the invariants checklist

12. FV MEV: create formal verification “MEV” type rules for all methods

13. Final report: prepare final report

Stateless vs statefull fuzzing

Now it’s time to understand how to check that all those invariants hold.

First of all, we should understand the difference between stateless and statefull fuzzing. In particular, we should think about what contract states those 2 fuzzing methods can reach.

Let’s take, for example, this smart contract:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 |

// SPDX-License-Identifier: UNLICENSED pragma solidity ^0.8.13; contract Counter { uint256 public number = 10; function increaseBy(uint256 newNumber) public { number += newNumber; } function decrement() public { number--; } } |

There’s a number state variable initially set to 10. Besides there’re 2 methods:

– increaseBy() which increases the number by a specified amount

– decrement() which decreases the number by 1

Now take a look at the following tests:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 |

// SPDX-License-Identifier: UNLICENSED pragma solidity ^0.8.13; import {Test} from "forge-std/Test.sol"; import {Counter} from "../src/Counter.sol"; contract CounterTest is Test { Counter public counter; function setUp() public { counter = new Counter(); } function testFuzz_increaseBy(uint256 x) public { uint256 numberBefore = counter.number(); // prevent overflow x = bound(x, 0, type(uint256).max - numberBefore); counter.increaseBy(x); assertEq(counter.number(), x + numberBefore); } function invariant_numberNot5() public { assertNotEq(counter.number(), 5); } } |

If you run forge test --match-test testFuzz_increaseBy, you’ll get the following output:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

Ran 1 test for test/Counter.t.sol:CounterTest [PASS] testFuzz_increaseBy(uint256) (runs: 256, μ: 17465, ~: 17537) Suite result: ok. 1 passed; 0 failed; 0 skipped; finished in 7.57ms (6.62ms CPU time) Ran 1 test suite in 134.81ms (7.57ms CPU time): 1 tests passed, 0 failed, 0 skipped (1 total tests) |

The testFuzz_increaseBy is a stateless test (fuzz test in terms of foundry). It actually checks only 2 contract states: before calling increaseBy() and after.

Now run forge test --match-test invariant_numberNot5. You’ll get this output:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

Ran 1 test for test/Counter.t.sol:CounterTest [FAIL: invariant_numberNot5 replay failure] [Sequence] (original: 5, shrunk: 5) sender=0xbCf0f377E28b2Be7f74477Cae95Bd0b444FCe172 addr=[src/Counter.sol:Counter]0x5615dEB798BB3E4dFa0139dFa1b3D433Cc23b72f calldata=decrement() args=[] sender=0x000000000000000000000000000000000000111D addr=[src/Counter.sol:Counter]0x5615dEB798BB3E4dFa0139dFa1b3D433Cc23b72f calldata=decrement() args=[] sender=0x000000000000000000000000000000000000045B addr=[src/Counter.sol:Counter]0x5615dEB798BB3E4dFa0139dFa1b3D433Cc23b72f calldata=decrement() args=[] sender=0x0000000000000000000000000000000000001B06 addr=[src/Counter.sol:Counter]0x5615dEB798BB3E4dFa0139dFa1b3D433Cc23b72f calldata=decrement() args=[] sender=0x36A6f2224DE35354E500de103eD343dF5aBA671F addr=[src/Counter.sol:Counter]0x5615dEB798BB3E4dFa0139dFa1b3D433Cc23b72f calldata=decrement() args=[] invariant_numberNot5() (runs: 1, calls: 1, reverts: 1) Suite result: FAILED. 0 passed; 1 failed; 0 skipped; finished in 103.25ms (102.69ms CPU time) |

The invariant_numberNot5 is a statefull test (invariant test in terms of foundry). The invariant defined in the invariant_numberNot5 test checks that the number state variable can’t be 5. Foundry simply calls all of the contract methods in a random order and checks afterwards whether the number state variable is 5 or not. So, foundry actually preserves the contract state between arbitrary contract method calls. That is why foundry is able to show us a counterexample in the console output that if the decrement() method is called 5 times, then the number state variable will be 5, which breaks the invariant. Obviously, with random method calls, foundry allows us to reach way more contract states than a plain stateless / fuzz test.

Statefull fuzzing vs formal verification

Now let’s understand the difference between statefull fuzzing and formal verification.

Let’s take this contract as an example:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

// SPDX-License-Identifier: UNLICENSED pragma solidity ^0.8.13; contract CounterFV { uint256 public number; function increment(uint256 x) public { if (x == type(uint256).max / 2) { number++; } } } |

It has the only state changing method increment(). If the provided x parameter is type(uint256).max / 2 then it clearly must increment the number state variable by 1.

For statefull fuzzing, let’s take this test:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 |

// SPDX-License-Identifier: UNLICENSED pragma solidity ^0.8.13; import {Test} from "forge-std/Test.sol"; import {CounterFV} from "../src/CounterFV.sol"; contract CounterFVTest is Test { CounterFV public counterFV; function setUp() public { counterFV = new CounterFV(); } /// forge-config: default.invariant.runs = 10000 function invariant_numberNot1() public { assertNotEq(counterFV.number(), 1); } } |

The invariant_numberNot1 test checks that the number state variable is never 1, which obviously can not hold. If you run forge test --match-test invariant_numberNot1, you’ll get this output:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

Ran 1 test for test/CounterFV.t.sol:CounterFVTest [PASS] invariant_numberNot1() (runs: 10000, calls: 5000000, reverts: 0) ╭-----------+-----------+---------+---------+----------╮ | Contract | Selector | Calls | Reverts | Discards | +======================================================+ | CounterFV | increment | 5000000 | 0 | 0 | ╰-----------+-----------+---------+---------+----------╯ Suite result: ok. 1 passed; 0 failed; 0 skipped; finished in 63.92s (63.91s CPU time) |

The invariant test ran for ~1 minute, performed 10000 runs and could not break the invariant, although it’s obvious that the invariant can be broken.

Next, let’s see how formal verification with Certora handles the same invariant.

Create a CounterFV.conf certora config file:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

{ "files": [ "src/CounterFV.sol" ], "verify": "CounterFV:certora/CounterFV.spec", "rule_sanity": "basic", "optimistic_loop": true, "msg": "CounterFV", } |

Create a certora rule for the “number can not be 1” invariant:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

// Number can not be 1 rule high_numberNot1() { method f; env e; calldataarg args; require number(e) != 1, "Invariant holds initially"; f(e, args); assert number(e) != 1; } |

If you run certoraRun certora/CounterFV.conf, you’ll get this certora formal verification result: https://prover.certora.com/output/8691664/40ce644d4d8445dab7d68fbe63e51941/?anonymousKey=ccf88867e372884e4f9cd28d0de7f1f771f95361

You can see that Certora found a counterexample of x == 2^255 - 1, which breaks the invariant. It took 44 seconds for Certora to break the invariant, while statefull fuzzing couldn’t break it in a minute.

Here is a list of the pros and cons of using the Certora Prover.

Pros:

1. Certora operates on all possible values which state variables can be set to. Let that sink in. When you create a certora rule or invariant, they start at an arbitrary contract state, then perform some state changes and finally assert that the invariants are not broken. It’s your job to understand if the final contract state is reachable; the better you understand the protocol, the faster you can handle false positive counterexamples. Compare it with the statefull fuzzing where random methods are called with random parameters, statefull fuzzing can’t reach every possible state like Certora (or other formal verification tools).

2. Generally (this is a heuristic), if your statefull test takes more than 5 minutes to execute, then you can rewrite it in Certora and (with the help of summaries) get a faster result which covers all possible contract states instead of relying on statefull fuzzing randomness.

3. Certora saves time in a protocol contracts setup with complex architecture. With statefull fuzzing, you should create handlers or mocks for all 3rd party integrations (like uniswap, chanlink, layerzero, etc…). With Certora, you “simply” bring all of the contracts into the Certora contracts scene, probably summarise some of the methods, and you’re good to go.

Cons:

1. Steep learning curve. Grasping https://docs.certora.com/en/latest/ and https://github.com/Certora/Examples takes quite a while.

2. Redundant require statements may cause your invariants to be unsound, thus leaving bugs unnoticed in the smart contract code.

3. Too many false positive counterexamples and execution time. Sometimes it gets annoying to write another require() statement for a clearly unreachable contract state and wait for another 5 minutes for the Certora backend to finish verifying the specs.

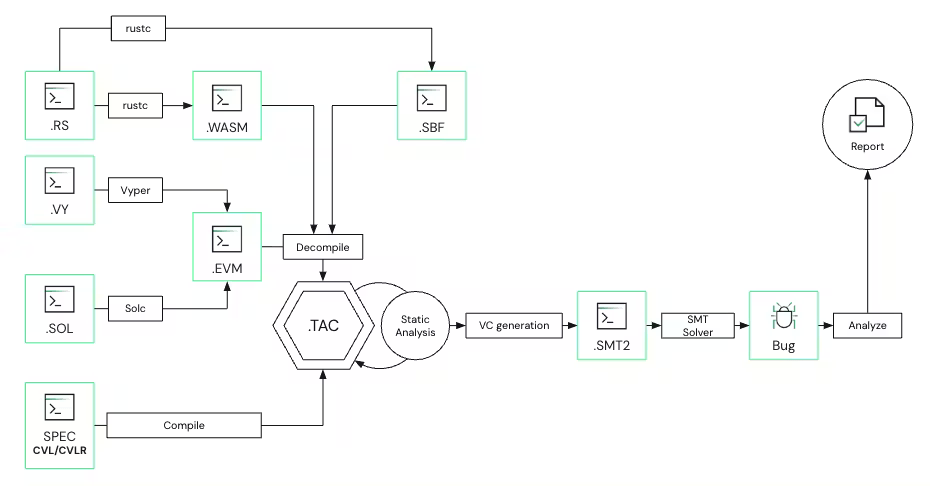

How Certora Prover works

Check the Certora Prover architecture diagram:

1. Blockchain specific compiler (solc, rustc, vyper) turns a smart contract into bytecode (by the way Certora Prover also helps in finding compiler bugs).

2. A decompiler maps the blockchain specific bytecode into instructions over scalar variables called “registers”. This representation is called TAC.

3. A static analysis algorithm then infers sound invariants about the code, drastically simplifying the verification task.

4. Then, the VC (Verification Condition) generator outputs a set of mathematical constraints which describe the conditions under which the program can violate the rules.

5. Certora Prover invokes off-the-shelf SMT solvers (Z3, CVC5, Yices, Vampire) that automatically search for solutions to the mathematical constraints which represent violations of the rules. These solvers can fail in certain cases by timing out with an inconclusive answer.

6. Certora Prover takes the result from the solver, processes it to generate a detailed report, and presents it to the client/user of the prover.

Example

Let’s, for example, take this smart contract:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 |

// SPDX-License-Identifier: UNLICENSED pragma solidity ^0.8.13; import {Ownable} from "openzeppelin-contracts/contracts/access/Ownable.sol"; import {Math} from "openzeppelin-contracts/contracts/utils/math/Math.sol"; import {ERC20Mock} from "./ERC20Mock.sol"; /** * @notice Bank contract */ contract Bank is Ownable { using Math for uint256; // Deposited asset ERC20Mock public asset; // APR in BPS, 1 BPS == 0.01% uint256 public aprBps; // Deposit fee in BPS, 1 BPS == 0.01% uint256 public feeBps; // Total fees available for collection by the owner uint256 public totalFees; // Total amount of deposited assets uint256 public totalDepositedAmount; // Amount of tokens deposited by a particular user mapping(address user => uint256 depositedAmount) public userDepositedAmount; // Timestamp when user's deposit can be withdrawn, set to 0 of there's no active deposit mapping(address user => uint256 unlockTimestamp) public userUnlockTimestamp; // BPS precision uint constant PRECISION = 10_000; // Error error AlreadyDeposited(); error EmptyBalance(); error Locked(); error ZeroAmount(); /** * @notice Constructor * @param _asset Bank deposit asset * @param _aprBps APR in BPS * @param _feeBps Protocol fee in BPS */ constructor(address _asset, uint256 _aprBps, uint256 _feeBps) Ownable(msg.sender) { asset = ERC20Mock(_asset); aprBps = _aprBps; feeBps = _feeBps; } //========== // Public //========== /** * @notice Deposits assets to the contract * @param amount Amount of assets to deposit */ function deposit(uint256 amount) external { // validation if (userDepositedAmount[msg.sender] > 0) revert AlreadyDeposited(); if (amount == 0) revert ZeroAmount(); // effects uint256 fee = getFee(amount); userDepositedAmount[msg.sender] = amount - fee; userUnlockTimestamp[msg.sender] = block.timestamp + 365 days; totalFees += fee; totalDepositedAmount += userDepositedAmount[msg.sender]; // interactions asset.transferFrom(msg.sender, address(<em>this</em>), amount); } /** * @notice Withdraws all assets with a yield after 365 days */ function withdraw() external { // validation uint256 depositedAmount = userDepositedAmount[msg.sender]; if (depositedAmount == 0) revert EmptyBalance(); if (userUnlockTimestamp[msg.sender] > block.timestamp) revert Locked(); // effects userDepositedAmount[msg.sender] = 0; userUnlockTimestamp[msg.sender] = 0; totalDepositedAmount -= depositedAmount; uint256 yield = getYield(depositedAmount); // interactions asset.mint(msg.sender, yield); asset.transfer(msg.sender, depositedAmount); } /** * @notice Withdraws all assets without a yield */ function withdrawEmergency() external { // validation uint256 depositedAmount = userDepositedAmount[msg.sender]; if (depositedAmount == 0) revert EmptyBalance(); // effects userDepositedAmount[msg.sender] = 0; userUnlockTimestamp[msg.sender] = 0; totalDepositedAmount -= depositedAmount; // interactions asset.transfer(msg.sender, depositedAmount); } //========= // Owner //========= /** * @notice Collects all available fees */ function collectFees() external onlyOwner() { // validation uint256 totalFeesCached = totalFees; if (totalFeesCached == 0) revert EmptyBalance(); // effects totalFees = 0; // interactions asset.transfer(msg.sender, totalFeesCached); } /** * @notice Rug pulls the contract, transfers all assets to the owner * @dev Serves as an example of broken solvency invariant */ function rugPull() external onlyOwner() { asset.transfer(msg.sender, asset.balanceOf(address(<em>this</em>))); } //=========== // Helpers //=========== /** * @notice Returns fee amount * @param amount Amount */ function getFee(uint256 amount) public view returns (uint256) { return amount.mulDiv(feeBps, PRECISION); } /** * @notice Returns yield amount * @param amount Amount */ function getYield(uint256 amount) public view returns (uint256) { return amount.mulDiv(aprBps, PRECISION); } } |

In the Bank smart contract, users are able to:

– deposit() (i.e stake) ERC20 assets for 365 days and pay a deposit fee

– withdraw() deposited assets with a yield after the staking period is over

– call withdrawEmergency() to withdraw deposited assets immediately without a yield

Contract owner is able to:

– collectFees()

– rugPull() all contract assets, placed as an example of a broken solvency invariant

A typical user flow example:

1. User deposits 100 ERC20 tokens with 10% APR and 1% protocol fee

2. 99 ERC20 tokens goes to deposit, 1 ERC20 token goes to fees

3. After a year, the user withdraws the deposited assets

4. User gets 108.9 ERC20 tokens (10% APR)

5. Owner calls collectFees() and gets 1 ERC20 fee token

We start formal verification with “unit test” type invariants for all contract methods.

For the deposit() method, we should check that:

1. deposit() updates storage as we expect

2. deposit() does not revert unexpectedly

3. deposit() does not affect 3rd parties (i.e. other users’ deposits)

4. deposit() additivity (since the user can have only 1 deposit at a time, this check can be skipped)

We create the following certora rules for the deposit() method:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 |

// `deposit()` updates storage as expected rule unit_deposit_integrity() { env e; applySafeAssumptions(e); uint256 amount; uint256 fee = getFee(e, amount); uint256 userDepositedAmountBefore = userDepositedAmount(e, e.msg.sender); uint256 userUnlockTimestampBefore = userUnlockTimestamp(e, e.msg.sender); uint256 totalFeesBefore = totalFees(e); uint256 totalDepositedAmountBefore = totalDepositedAmount(e); uint256 senderBalanceBefore = token.balanceOf(e, e.msg.sender); uint256 contractBalanceBefore = token.balanceOf(e, currentContract); deposit(e, amount); uint256 userDepositedAmountAfter = userDepositedAmount(e, e.msg.sender); uint256 userUnlockTimestampAfter = userUnlockTimestamp(e, e.msg.sender); uint256 totalFeesAfter = totalFees(e); uint256 totalDepositedAmountAfter = totalDepositedAmount(e); uint256 senderBalanceAfter = token.balanceOf(e, e.msg.sender); uint256 contractBalanceAfter = token.balanceOf(e, currentContract); assert userDepositedAmountAfter == amount - fee; assert userUnlockTimestampAfter == require_uint256(e.block.timestamp + SECONDS_IN_YEAR()); assert totalFeesAfter == require_uint256(totalFeesBefore + fee); assert totalDepositedAmountAfter == require_uint256(totalDepositedAmountBefore + amount - fee); assert senderBalanceAfter == senderBalanceBefore - amount; assert contractBalanceAfter == require_uint256(contractBalanceBefore + amount); } // `deposit()` reverts when expected rule unit_deposit_revertConditions() { env e; applySafeAssumptions(e); uint256 amount; bool isEtherSent = e.msg.value > 0; bool hasUserAlreadyDeposited = userDepositedAmount(e, e.msg.sender) > 0; bool isAmountZero = amount == 0; bool hasContractEnoughAllowance = token.allowance(e, e.msg.sender, currentContract) >= amount; bool hasUserEnoughBalance = token.balanceOf(e, e.msg.sender) >= amount; bool isTotalFeesOverflow = totalFees(e) + getFee(e, amount) > max_uint256; bool isUnlockTimestampOverflow = e.block.timestamp + SECONDS_IN_YEAR() > max_uint256; bool isFeeTooBig = getFee(e, amount) > amount; bool isTotalDepositedAmountOverflow = totalDepositedAmount(e) + amount - getFee(e, amount) > max_uint256; bool isExpectedToRevert = isEtherSent || hasUserAlreadyDeposited || isAmountZero || !hasContractEnoughAllowance || !hasUserEnoughBalance || isTotalFeesOverflow || isUnlockTimestampOverflow || isFeeTooBig || isTotalDepositedAmountOverflow; deposit@withrevert(e, amount); assert lastReverted <=> isExpectedToRevert; } // `deposit()` does not affect 3rd party entities rule unit_deposit_doesNotAffect3rdPartyEntities() { env e; applySafeAssumptions(e); uint256 amount; address otherUser; require otherUser != currentContract && otherUser != token && otherUser != e.msg.sender; uint256 otherUserBalanceBefore = token.balanceOf(e, otherUser); deposit(e, amount); uint256 otherUserBalanceAfter = token.balanceOf(e, otherUser); assert otherUserBalanceBefore == otherUserBalanceAfter; } |

We keep creating “unit test” type rules for all contract methods.

Next, we go to “high level” invariants. Let’s start with the access control invariant “owner protected methods are callable only by the contract owner”:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 |

//---------------------------------------- // Methods are called by expected roles //---------------------------------------- rule high_accessControl() { env e; method f; calldataarg args; f(e, args); assert ( f.selector == sig:collectFees().selector || f.selector == sig:rugPull().selector ) => e.msg.sender == owner(e); } |

Let’s also add the solvency invariant:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 |

//---------------------------------------- // Protocol solvency //---------------------------------------- rule high_solvency() { env e; applySafeAssumptions(e); require token.balanceOf(e, currentContract) == totalDepositedAmount(e) + totalFees(e); method f; calldataarg args; if (f.selector == sig:deposit(uint256).selector) { uint256 amount; require token.balanceOf(e, currentContract) + amount <= max_uint256, "Prevent overflow"; deposit(e, amount); } else { f(e, args); } assert token.balanceOf(e, currentContract) == totalDepositedAmount(e) + totalFees(e); } |

You may find all Certora specs here.

Next, create a certora config file (ERC20Mock source code is here):

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

{ "files": [ "src/Bank.sol", "src/ERC20Mock.sol", ], "verify": "Bank:certora/Bank.spec", "link": [ "Bank:asset=ERC20Mock" ], "parametric_contracts": [ "Bank" ], "rule_sanity": "basic", "optimistic_loop": true, "optimistic_hashing": true, "msg": "Bank", } |

And finally, run the certora config with certoraRun certora/Bank.conf. You’ll get this certora report: https://prover.certora.com/output/8691664/d9debc82b644401e859f2387273d2298/?anonymousKey=052aa3b31101c06e4ea7511949e55773f7014b20

You may see that all “unit test” rules are proved, which means that all of the contract methods:

1. Change storage as expected

2. Do not revert unexpectedly

3. Do not affect other entities unexpectedly

The high_accessControl rule is also proven, which means that access control works as expected.

But, the high_solvency rule, which checks the protocol solvency invariant, is violated for the rugPull() method, which is something that we were expecting.

The next steps for the Bank contract are to meticulously follow the invariants checklist and prove that none of the other “high” level invariants are broken. For example, some of the weird ERC20 tokens (in particular, the ones with the transfer fees) are clearly not supported.

Summary

In this blog post, we discovered how to perform a comprehensive smart contract audit with the help of formal verification using the Certora Prover. This audit approach (with a bit of luck) can find 100% of “high” severity issues in smart contracts, although it takes a really significant amount of time, but for protocols with a huge TVL (ex: aave) this is a “must have” feature.

The final note is about modern LLMs. Humans are clearly missing bugs. Modern LLMs can only find “low hanging” bugs and also can’t find all security issues in a smart contract. Instead of training LLMs to find bugs in smart contracts, it’s better to train them to build correct invariants and let humans verify those invariants and counterexamples.

Full source code can be found at https://github.com/ryzhak/smart-contract-audit-flow.

Thank you for reading.